Für die deutsche Version bitte hier klicken.

History shapes cycling in our everyday lives in many ways. The roads and paths on which we are travelling exert a particularly sustainable form of influence. With slight regional deviations, most of the current road infrastructure is geared towards motorised private transport. Responsible for this are, on the one hand, a mix of past ideas of progress, imaginations of mobility and traffic policies derived from it. The infrastructure that has resulted from this complex situation are the streets on which we are moving today. On the other hand, the interpretations and ideas that have set in with the use of this infrastructure shape us today. Both these imaginations and the material infrastructure are inert and they vehemently oppose rapid change.

The Taken-for-Grantedness of Infrastructure

Once built, the road infrastructure seems almost naturally given and we forget that deliberately made decisions, unconscious routines and internalized ideas have been involved in their creation. The present condition seems as if it had always been like this and will remain so in the future. Therefore, the barely questioned opinion prevails that the road is mainly for cars, trucks or buses and neither pedestrians nor cyclists should take a lot of space on it. The latter may only use the road at the very edge and one behind the other.

Picture Credit: Max A. Wyss, ©Stiftung Fotodok

Cars and trucks are bigger and faster than bikes so of course they need more space on the road. Wider roads are then the obvious answer to wider cars. Building new roads or creating more tracks is the obvious reaction to increasing traffic. These measures seem to be in the nature of things and they require almost no justification. It is discussed where new roads should be built or whether a new road should be hidden in a tunnel. Questioning such measures results in disapproval rather than understanding.

Source: https://youtu.be/cvvoXuJ1A-A

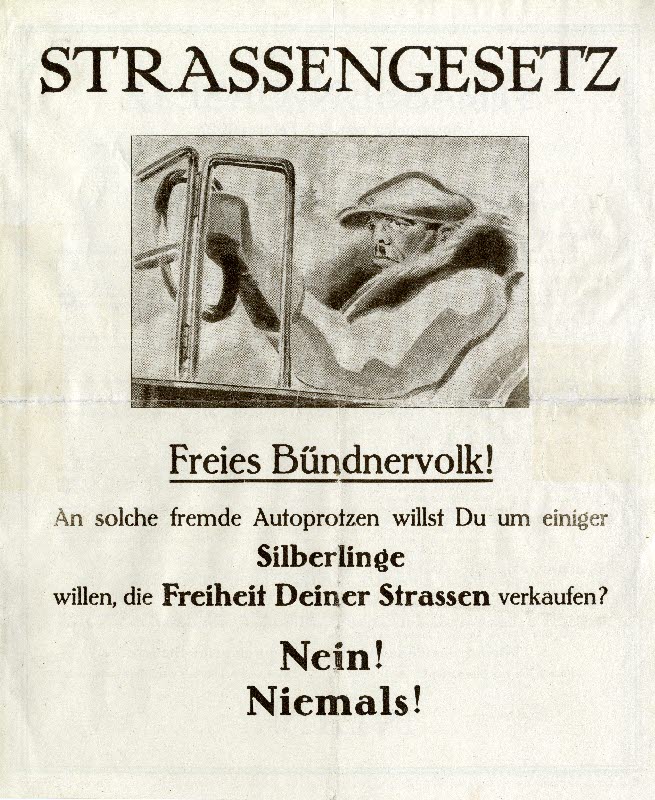

The history of transport and mobility shows quite the contrary: The streets have not always been there for cars. The first promoters of modern road construction were passionate cyclists who were not satisfied with the rough dust tracks. While it still only sporadically appeared on the roads, the automobile was by no means welcomed on the streets in the early twentieth century. In England, in 1903, a conservative parliamentarian argued that „the roads of England were made for the people, and they should not be monopolised by a certain section, no matter what they belong to the poor or the rich.” The canton of Grisons in Switzerland officially prohibited its use. The ban on cars was lifted only in 1925 and two years later supplemented by a new road law. The opponents already attempted to mobilise with xenophobic arguments not uncommon in the political sphere today.

[Free people of Grisons! Do You want to sell the freedom of your streets to such bigwigs for the sake of some silverlings? No! Never!]

Picture Credit: Rätisches Museum Chur, H1982.139.1

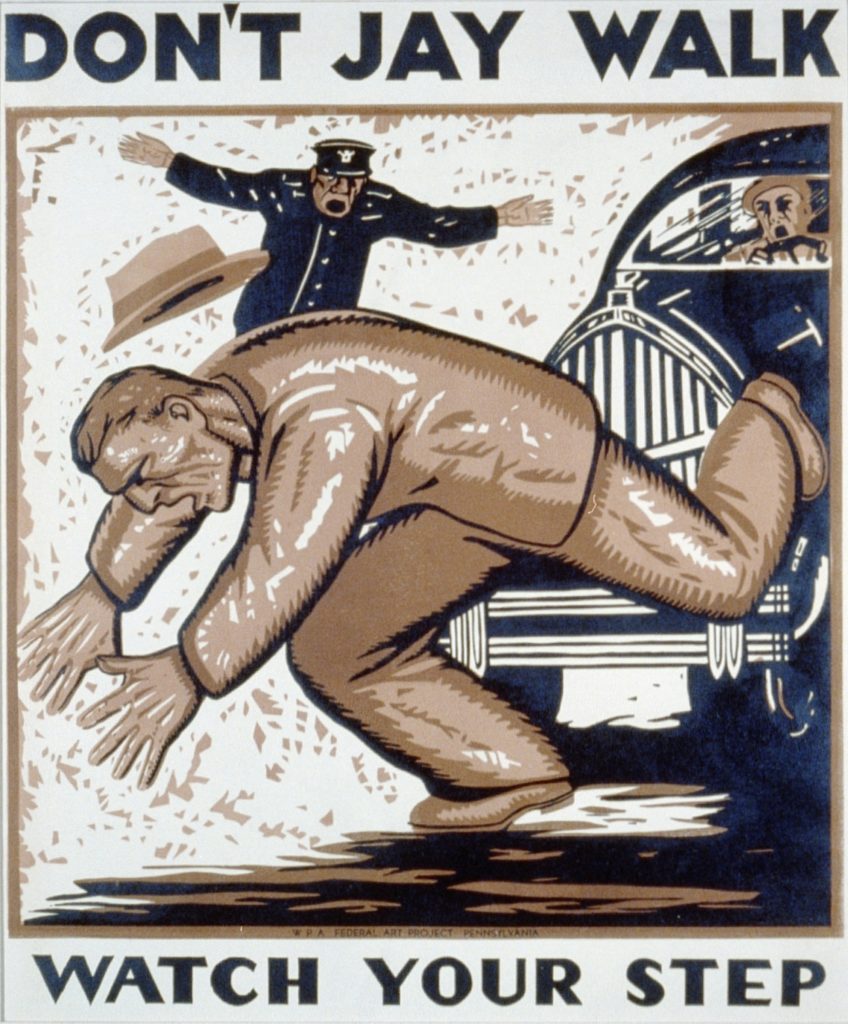

It required coordinated action by politicians and the car industry to ban cyclists, but also pedestrians, carts, trams or even buses from the streets. Similar to the invention of the seemingly careless “Smombie” today, not quite 100 years ago the “Jaywalker” and playing children were cautioned and forced off the street. Since then, the cars have the right of way. On foot, one should only enter the road at designated places — such as zebra crossings. In the meantime, this order has been reinforced with fines and reprimands by the police or disapproving looks from fellow human beings.

Picture Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Revisions in Transport Policy and the Mountain Bike

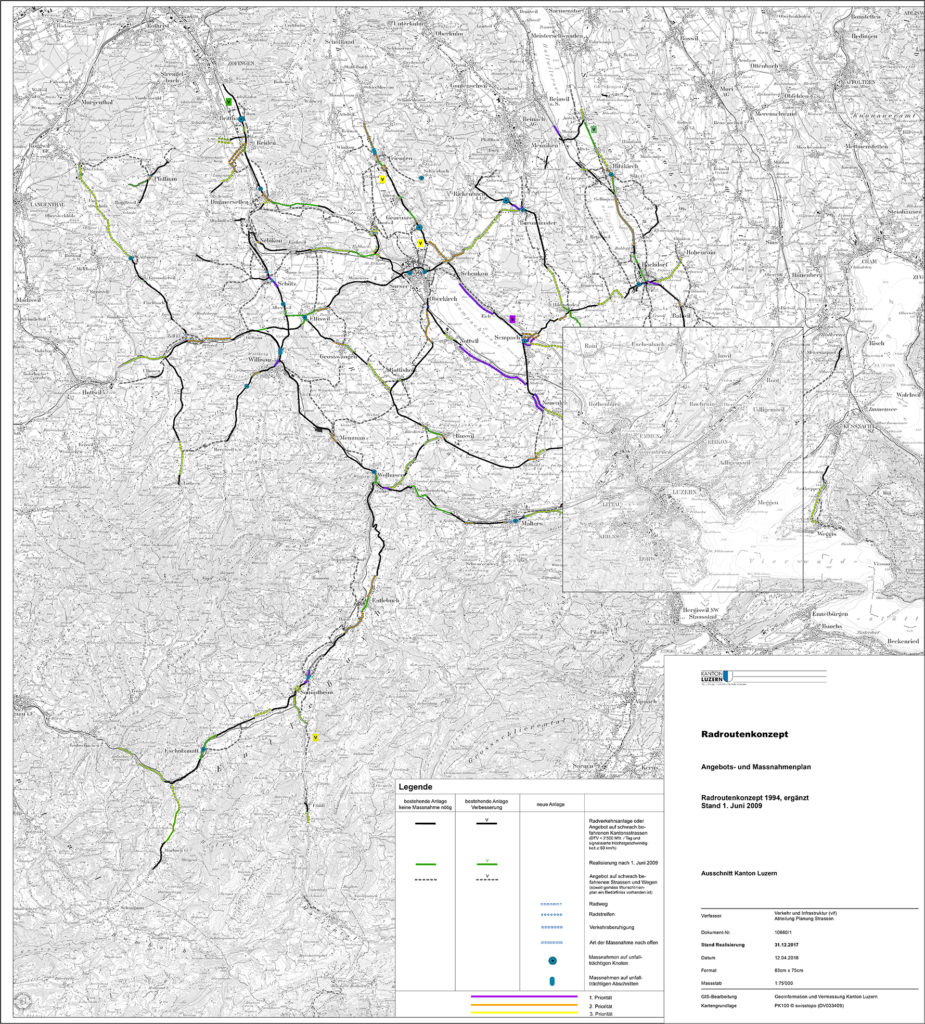

There are different reactions to this situation: For several decades, different actors have been trying to trigger a revision of transport policy. In view of the inertia of infrastructure and cultural ideas, they had varying degrees of success: While cities such as Amsterdam and Copenhagen and since the turn of the millennium big cities like New York and London have become global role models for cycling, the cyclists in my canton of residence are now waiting in the third decade for the full implementation of the cycle route concept that was adopted in 1994.

Source: https://vif.lu.ch/aufgaben/radverkehr

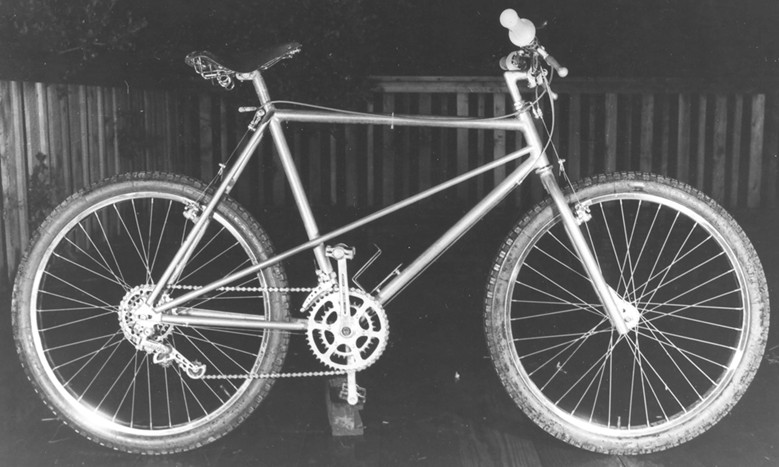

Another answer seems to have been exceedingly successful: People began to look for fun off the beaten track. Since the late 1970s the mountain bike has been established as an important part of the modern cycling culture. It stands for pleasure and leisure in nature. Established tourist regions such as Grison or Central Switzerland even recognise it as a way of securing revenues from tourism in the long term.

Picture Credit: http://sonic.net/~ckelly/Seekay/mtbwelcome.htm

The success of the mountain bike may also lie in the fact that it has hardly touched the sovereignty of the automobile on the road. On the contrary, the car and the mountain bike seem to be perfect complements. By car or camper, the bike can be easily transported to the tourist region or the beginning of the trail. At the same time, the bicycle is firmly anchored in the leisure sector and not perceived as a transport option for everyday life. Those who want to bike to work seem to have little advantage from the mountain bike boom — apart from significant technical innovations such as suspension and disc brakes.

Alternative Routes: Around Lake Sempach on Quiet Roads

Another solution that is equally suitable for everyday life as for pleasure riding is to search for and find low-traffic roads. Anyone who has ever been travelling on official cycle routes — like the ones from SwitzerlandMobility — and wanted to get ahead quickly, knows how to compromise. The routes were selected from the existing road network so that one is not exposed to heavy traffic. The direct route is usually not suitable for cyclists or only suitable for traffic-hardened and self-confident cyclists. Therefore, as a user of the proposed routes, one must always take prolonging detours and diversions. But if you are travelling as a recreational cyclist, it may be just the charm of the bike tour. If you invest a little time, you will find countless opportunities for an attractive cycling route in the available network of small country lanes.

In this spirit, I have set myself the goal to cycle round Lake Sempach, a scenic bike ride in the canton of Lucerne, on an alternative route. The usual lap around the lake is situated on traffic laden overland roads. On the south side of the lake, between Nottwil and Emmenbrücke, you find yourself on a nerve-wracking section right on the narrow street with cars and lorries zipping by. This road was already envisaged in the cantonal cycle route concept of 1994 with the highest priority for the addition of a cycle path. However, this section does not have a bike path or a continuous cycle lane to this day. Cyclists are exposed to dangerously close passing cars for about ten kilometres.

While planning, I had the premises in mind that the route should be low in traffic and still mostly on asphalt. Not unnecessarily taking up space from pedestrians was my second condition. Thus, the direct route on the narrow gravel road on the south of the lake was rapidly eliminated. I had to reckon with detours and ascents. At the same time this offered the opportunity to add sights to the route. After some planning, I have tried the following:

I leave Lucerne on the bike path along the Reuss in the direction of Emmen. In Emmen I turn left and cross the runway of the military airfield in Emmenfeld. Planned as a civil airfield for the development of the tourist region around Lucerne in 1924, the project was taken over by the military and built to relieve the fast-growing air force. After 15 years of planning and construction, the airfield was opened in 1939. The Swiss Air Forces’ first military jet — a vampire — landed in Emmen in 1949. In “Operation Snowball” the British flying ace John Cunningham delivered the last aeroplane to Emmen. The name derives from the fact that he had his skis attached to the tail of the aircraft in order to take a winter vacation later on.

Picture Credit: ETH-Library Zurich, Image Archive

After crossing the runway there is a short climb leading past the barracks to Rothenburg. At Wegscheiden [lit. „Path-Forken“] — nomen est omen – I turn off towards Sempach.

The road leads past the motorway service area in Neuenkirch and the Swiss Pig Breeding Association into the medieval town of Sempach.

On my ride through the small town, I was astonished how much space is left to cars. The speedometer in the middle of the old town seems to speak for itself in this regard. Somewhat disappointed I left Sempach quickly on the north side through the Gate to Sursee.

The „Sursee Gate” was reconstructed only in the 1980s in medieval style. Something that is not uncommon for seemingly medieval cities. On aerial photographs from 1957 the northern gate is not yet to be discovered. But one can already make out the cars which were parked in the city.

Picture Credit: ETH-Library, Wikimedia Commons

Outside the town I ride straight over the roundabout. The road is narrow and heavy on traffic and although this section is an official route of SwitzerlandMobility, it is missing a bicycle lane. Therefore, I conquer the surprisingly steep climb on the sidewalk. For my safety’s sake, it’s the only time I have to compromise on this tour.

However, the short climb is worth its while. Turn left at the red signpost of SwitzerlandMobility and after a few meters you will reach a tranquil hamlet.

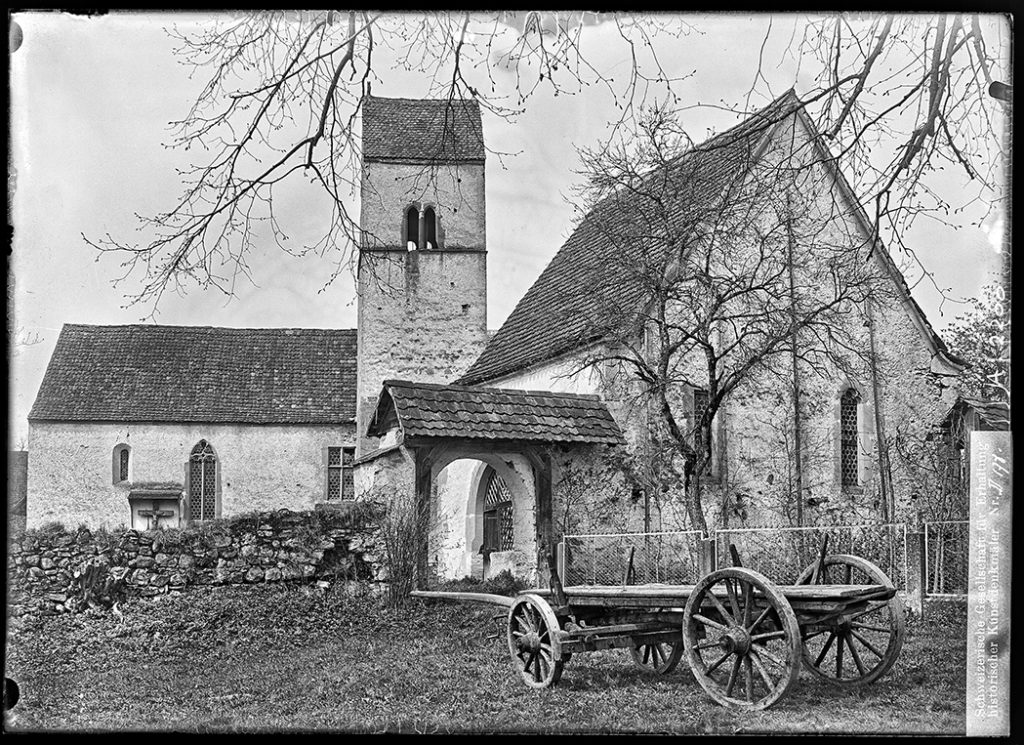

The settlement houses the picturesque church of St. Martin on Kirchbühl. The present building dates from the 13th century, making the church one of the oldest in the canton of Lucerne. Until the nineteenth century, it was the parish church of Sempach, but because of its remote location it has lost its importance early on. That is why it seems to have survived the last centuries surprisingly untouched. Thus, a restoration in the years 1901-1911 could easily restore the “original” medieval condition. The interior walls are painted with well-preserved frescoes from the fourteenth century. Due to their completeness they are apparently of high cultural and historical importance.

Picture Credit: Swiss National Library, EAD-6761, Wikimedia Commons

After a few contemplative minutes and a rest, I got on a dirt road just a short distance behind the church. I felt transported back to the time of the early cyclists, for whom such roads had been the norm. When dry, this section can be easily mastered with any type of machine, even a racing bike.

Having passed Eich, the road ascends again. Instead of turning right and taking the cycle route that clings to the motorway, I rode further up and turned at the roundabout „Eichhof“. On the left-hand side, I entered a narrow street with a ban on driving cars and motorcycles.

This road offers a beautiful vista of Lake Sempach, the Pilatus and the extending mountain range. The motorway is hidden from sight and hearing. It does not reappear until a short descent takes you back to the lake. From there, the route takes you along the lake to Sursee, into the next medieval town.

Although Sursee can be entered by car and parking is available, the town looks tidier and appears more hospitable than its counterpart on the southern side of the lake. The place invites for taking a rest, to explore the narrow streets and to get a feel of the seemingly medieval atmosphere. At first sight hardly anything seems to have changed in the last hundred years, except for the wagons, which gave way to cars and a new road surface.

Picture Credit: ETH-Library, Image Archive: Fel_003507-RE

From the northern end of the lake, the route leads back to the south. Unspectacular but with a sense of security I ride on the cycle lane and a little later on a segregated cycle path to Nottwil. On the cycle path children were passing me in the opposite direction, there were older men on ladies’ bicycles and racers with aero helmets on time-trial machines. This diversity seems to be an encouraging sign of a high sense of safety on the bike path. Nottwil houses the campus of the Swiss Paraplegic Foundation, which is dedicated to the rehabilitation of people with spinal cord injury. However, just in front of the Paraplegic Centre the bike path ends and the alternative route to Neuenkirch and Emmenbrücke begins.

It’s inevitable to climb a few meters, but the road is narrow and hardly travelled. The scenery high above Lake Sempach becomes very bucolic.

The route passes farms and busy peasantry. The names of the hamlets become as idyllic as the landscape. I cycle on a narrow road through the Sparre and the Homel woods and get to Windblosen [lit. „Wind-Blowen“], with an awarded cheese factory that produces Emmentaler.

From there, I travel on to Ausserwindblosen [lit. „Outer-Wind-Blowen“] and the Ankeland [lit. „Butter-Land“] to Hunkelen. If riding a mountain bike, you can also choose the direct route through the Windblosenwald and thus avoid additional altitude.

A short descent leads down to Hellbühl and on the busy main road, which I leave, however, after roughly 300 meters to the right. At Oberlimbach, the scenery changes and it is contemplative again.

On the Littauerberg the road remains narrow, but the traffic increases to my astonishment. A cursory glance at the number plates shows that the drivers do not appear to live in the area. So, I am wondering why they’re taking this remote stretch.

It’s probably the cunning ones who think they’re going to move faster. Not to the delight of the cyclist, who has to cope with sometimes rather gruff driving and therefore sees his original project in danger. However, I quickly reach Emmenbrücke and the rural area transforms to suburbia immediately after a small hill.

Taking stock at the end of the tour is ambiguous: Compared to the direct route on the trunk road you make a few more kilometres and some moderate climbing. As a bicycle commuter this would undoubtedly annoy me, but as I am just rambling, I make a virtue out of necessity. I was exploring some sights in the countryside of Lucerne away from heavy traffic. However, when I arrived again at the outskirts of Lucerne, I am immediately reminded of how marginalised cyclists are on the street. As soon as the automobile traffic starts to pick up again, the cyclists will only be left on the outer edge of the road. The sometimes very close overtaking manoeuvres give the impression that this happens only extremely reluctantly. Nevertheless, there is a silver lining for the circumnavigation of the Sempachersee by bike: In 2017, the continuous cycle path from Nottwil to the Lohrensäge on the south side of Lake Sempach was again prioritised for reconstruction. Therefore, one may audaciously hope to be able to choose a more direct route soon.

Map